- Depreciation vs. Amortization: What is the Difference?

- Depreciation and Amortization (D&A): Definition

- What is the Definition of Depreciation?

- How is D&A Expense Recognized on Cash Flow Statement?

- How to Report Depreciation and Amortization for Tax Purposes

- How is D&A Recognized on Income Statement?

- Tangible Asset vs. Intangible Asset: What is the Difference?

- What is the Definition of Amortization?

- What is the Definition of Loan Amortization?

- How to Calculate Depreciation and Amortization (D&A)

- What are the Different Depreciation Methods?

- How Does D&A Expense Impact the Financial Statements?

Depreciation vs. Amortization: What is the Difference?

Depreciation and Amortization are accounting methods used to allocate the cost of an asset over its useful life, but the application pertains to different types of assets with distinct characteristics.

The depreciation expense reduces the carrying value of tangible, fixed assets (PP&E), which refer to physical assets that can be touched, such as machinery, tools, and buildings.

The periodic depreciation recognized reflects the gradual “wear and tear” of PP&E, which reduces in value with time and increased usage.

On the other hand, amortization expense reduces the carrying value of intangible assets with an identifiable life, such as intellectual property (IP), copyright, and customer lists.

- Depreciation is an accounting method used to allocate the cost of a tangible asset (e.g. machinery, equipment, buildings) over its useful life by gradually reducing its carrying value on the balance sheet.

- Amortization is an accounting method used to allocate the cost of an intangible asset (e.g. patents, copyrights) over its useful life by gradually reducing its carrying value on the balance sheet.

- Depreciation expense reduces the carrying value of tangible fixed assets on the balance sheet, while amortization expense reduces the carrying value of intangible assets.

- Both depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses that are added back to net income on the cash flow statement since no cash outflow occurred in the period.

Depreciation and Amortization (D&A): Definition

Under accrual accounting, depreciation and amortization (D&A) must be recognized by companies to abide by the matching principle, an accounting concept intended to “match” the timing of when an expense is recorded with the coinciding monetary benefit (i.e. revenue).

The underlying logic for recognizing depreciation and amortization in accrual accounting is practically the same—except for one distinction: the type of asset reduced in value.

The definitions of depreciation and amortization are each stated in the following list:

- Depreciation Definition ➝ The depreciation expense is recorded on the income statement to allocate the cost of purchasing a tangible asset (i.e. capital expenditure, or “Capex”) across its useful life assumption.

- Amortization Definition ➝ In contrast, the amortization expense is recorded to allocate the cost of intangible assets, such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights, over the useful life assumption.

In short, the depreciation of fixed assets and amortization of intangible assets gradually “spreads” the initial outlay of cash over the implied useful life of the asset.

The key difference between depreciation and amortization is the fact that the former reduces the carrying value of tangible assets (PP&E), while the latter causes the recorded value of intangible assets to decline.

Therefore, depreciation applies to tangible assets, whereas amortization relates to intangible assets, with comparable mechanics regarding the accounting impact on the financial statements.

What is the Definition of Depreciation?

The depreciation concept refers to the accounting process whereby the recorded carrying value of a tangible asset on the balance sheet is gradually reduced over time until the end of its useful life assumption.

The depreciation expense applies only to long-term tangible assets with a useful life in excess of one year (>12 months).

In comparison, current assets like inventory and office supplies—even if tangible—are not depreciated because the two short-term assets cycle out relatively quickly (<12 months).

- Useful Life ➝ The useful life of a fixed asset is the estimated number of years in which a fixed asset (PP&E) is anticipated to continue providing positive economic value on behalf of the company.

- Salvage Value ➝ Upon reaching the end of a fixed asset’s useful life assumption, the remaining balance of the fixed asset—formally termed the salvage value—is the residual value at which the asset could hypothetically be sold for in the open markets (“scrap value”).

How is D&A Expense Recognized on Cash Flow Statement?

The periodic recognition of depreciation is treated as a non-cash add-back on the cash flow statement (CFS), since no real cash movement occurred in the period.

Instead, the actual cash outlay occurred in the initial period when the company decided to purchase the long-term fixed asset (PP&E) or capital expenditure (Capex).

The standard accounting practice for most companies—exceptions aside, such as capital intensive companies—is to consolidate depreciation and amortization on the cash flow statement (CFS).

If the depreciation expense or amortization expense is disproportionally higher than the other, the norm is to recognize them separately, as exhibited by Alphabet (NASDAQ: GOOGL).

Depreciation Example (Source: GOOGL 10-K)

How to Report Depreciation and Amortization for Tax Purposes

In practice, most companies assume a salvage value of zero since depreciation is recognized on the income statement as an expense, thereby reducing the pre-tax income (and income taxes owed) on the income statement prepared under GAAP accounting standards.

- Higher D&A Expense ➝ Lower Pre-Tax Income (EBT) and Greater Tax Savings

- Lower D&A Expense ➝ Higher Pre-Tax Income (EBT) and Lower Tax Savings

In other words, recognizing a higher depreciation expense reduces the income tax liability recorded on the income statement for bookkeeping purposes.

Why? The income tax provision is a function of the applicable tax rate and the earnings before taxes (EBT), so reducing the pre-tax income results in fewer taxes owed.

On the balance sheet, the carrying value of the long-term fixed asset (PP&E), or book value, is reduced by the depreciation expense, reflecting the gradual “wear and tear” of the long-term assets.

The tangible asset could be assumed to carry some residual salvage value at the end of its useful life — albeit, most companies operate with the incentive to record a higher depreciation expense for tax purposes.

The standard method for the amortization schedule for intangible assets is on a straight-line basis, so the recognition of amortization abides by a uniform distribution (and thus, occurs at regular installments).

Note: The actual taxes paid by a company can be different from the tax expense recorded on the income statement.

How is D&A Recognized on Income Statement?

While seldom explicitly broken out on the income statement, the depreciation and amortization D(&A) expense is embedded within either the cost of goods sold (COGS) or operating expenses (Opex) section.

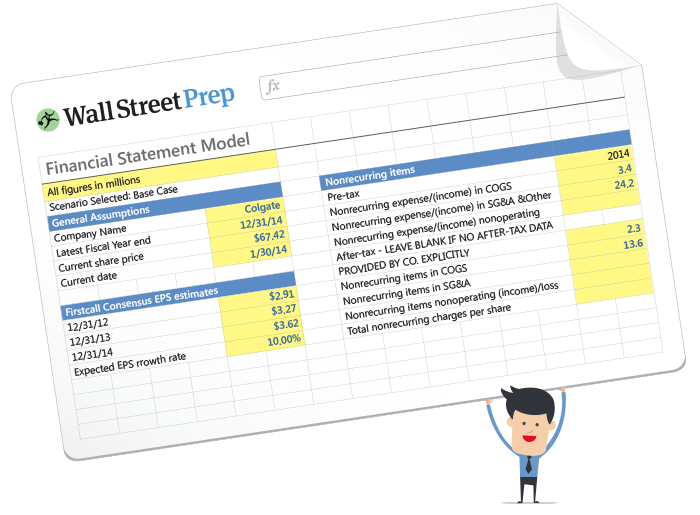

For example, the section where the D&A expense is recognized is highlighted in the screenshot below of Alphabet’s income statement.

Depreciation and Amortization (D&A) Example (Source: GOOGL 10-K)

Tangible Asset vs. Intangible Asset: What is the Difference?

Common examples of tangible assets that are capitalized and subsequently reduced by the depreciation expense on the income statement for bookkeeping purposes are as follows:

- Property

- Buildings and Facilities

- Machinery and Equipment

- Vehicles

- Furniture

- Computers and Electronics

Contrary to a common misconception, land is not permitted to be depreciated per U.S. GAAP accounting standards because of the implicit assumption that land has an infinite life.

On the other hand, the common examples of intangible assets with an identifiable life that are reduced by amortization for bookkeeping purposes include the following:

- Patents

- Intellectual Property (IP)

- Copyright

- Trademarks

- Customer Lists (and Client Relationships)

- Brand Recognition

Goodwill is not permitted to be amortized under U.S. GAAP for publicly-traded companies. However, public companies can recognize goodwill impairment as a downward adjustment to the recorded value on the balance sheet.

Certain assets are subject to impairment, which means that the carrying values stated on the balance sheet can be written down if deemed necessary to reflect the fair value of an asset, which could be tangible or intangible.

For instance, the recorded value of a company’s inventory, a current asset, can be written down partially on the books or completely wiped out based on the estimated fair value. The former is termed an “inventory write-down”, while the latter is called an “inventory write-off”.

What is the Definition of Amortization?

Amortization is the process of incremental reduction to an intangible asset via the recognition of the expense on the income statement over its expected useful life.

The premise of the amortization of intangible assets is that the consumption of an intangible asset over time causes its value to drop, which should be reflected in the financial statements.

Therefore, amortization refers to the accounting technique used to gradually reduce the book value of an intangible asset over a set period.

The amortization schedule refers to systematically recognizing the expense to amortize an intangible asset’s original value (or cost) over its useful life assumption.

Intangible assets, such as intellectual property, patents, trademarks, and copyrights, are non-physical items that retain value.

The amortization of intangible assets is mandatory for accounting and tax purposes to recognize the amortization expense at the same (or near) identical timing as the period in which the economic benefit was received.

The standard process by which an intangible asset is reduced in value is the straight-line method, with no salvage value assumed.

Like depreciation, the amortization expense reduces the income tax provision recorded on the current period’s income statement for bookkeeping purposes.

However, the amortization expense causes the carrying value of the corresponding intangible asset to decline, as opposed to a fixed asset.

What is the Definition of Loan Amortization?

On a side tangent, the term “amortization” could also refer to a loan repayment schedule, which carries a completely different meaning from the amortization schedule of an intangible asset.

The term “loan amortization” describes the loan payments issued by the borrower to a lender as part of a lending arrangement, such as a mortgage loan.

The loan principal is reduced with each incremental loan payment across the borrowing term until maturity, which is tracked using a loan amortization schedule.

The remaining principal, or loan balance, must be paid back in full by maturity, or else the borrower is in a state of default (and is now at risk of becoming insolvent).

The amortization of a loan is defined as the gradual reduction in the loan principal via periodic, scheduled payments to the lender, such as a bank.

The two components to calculate loan amortization are the principal and interest.

- Interest Expense ➝ The regular interest payments owed to the lender across the borrowing term, wherein the interest rate pricing is determined based on the risk profile of the borrower (i.e. cost of debt). The borrower’s interest payment is contingent on the interest rate set by the lending and the remaining principal balance. Therefore, the gradual reduction in the loan balance causes the periodic interest payment owed to the lender to decrease.

- Principal Amortization ➝ The principal amortization is the repayment of the original loan provided by the lender. Based on the terms set by the original lending agreement, the scheduled paydown of the loan principal can be entirely optional or mandatory. If the repayment is gradual, the borrower must issue a larger-sized payment at maturity to ensure the loan balance reaches zero at maturity. Conversely, the borrowing could have no mandatory amortization until maturity (“balloon payment”), which is more common for corporate bonds.

The loan amortization schedule varies case-by-case and is contingent on many factors, such as the structure of the lending arrangement, the agreed-upon terms, the current credit environment, economic conditions, and the borrower’s credit risk (or risk of default).

However, the original loan principal must be repaid in full at maturity—the date at which the original capital must be returned to the lender, as stated on the formal lending agreement—barring extraordinary circumstances.

Note: The periodic payment of interest on a loan does not reduce the principal balance.

How to Calculate Depreciation and Amortization (D&A)

The most common depreciation method—the straight-line method—gradually reduces the carrying value of a fixed asset (PP&E) across its useful life assumption.

The depreciation expense formula calculates the depreciable basis by subtracting the residual value from the purchase cost, which is then divided by the useful life assumption.

Where:

- Purchase Cost ➝ The total cost incurred by the company to acquire a fixed asset (PP&E) on the original date of purchase.

- Residual Value ➝ The estimated value of the asset as of the end of its useful life (or “scrap value”)

- Useful Life ➝ The estimated number of years the fixed asset (PP&E) is expected to continue providing positive economic utility.

The accumulated depreciation reduces the carrying value of fixed assets (PP&E) on the balance sheet until the balance winds down to zero. But of course, the company would likely allocate funds toward capital expenditures (Capex) before that could occur.

The amortization expense is calculated by dividing the historical cost of the intangible asset by the useful life assumption. However, the residual value assumption is usually set to zero, as the value of the intangible asset is expected to wind down to zero by the final period.

Where:

- Historical Cost of Intangible Asset ➝ The historical cost is the total amount paid on the initial date of purchase (i.e. M&A).

- Residual Value ➝ The residual value is the estimated value of a fixed asset at the end of its useful life span (“salvage value”).

- Useful Life ➝ The estimated number of years by which the intangible asset is expected to contribute positive economic value to the company.

What are the Different Depreciation Methods?

There is much more optionality in the depreciation method for fixed assets (PP&E), such as the straight-line method, declining balance, double declining balance (DDB), sum-of-the-years’ digits, and units of production method:

- Straight-Line Method ➝ Companies evenly depreciate assets throughout their useful life by subtracting the salvage value from the asset’s cost to determine the depreciable base (and thus, the annual depreciation expense recorded is equivalent each period).

- Declining Balance ➝ Companies apply accelerated depreciation early on in an asset’s useful life by multiplying the current book value by a fixed rate (%) that remains constant over the fixed asset’s useful life.

- Double Declining Balance Method ➝ Companies accelerate depreciation early in an asset’s life by doubling the straight-line rate and applying the rate to the current book value.

- Sum-of-the-Years’ Digits Method ➝ Companies sum the digits of an asset’s useful life and depreciate costs in proportion to the corresponding digit.

- Units of Production Method ➝ Companies estimate the anticipated usage of the fixed asset, such as the expected mileage for a vehicle, and then estimate the depreciation proportion based on projected usage (and historical data).

How Does D&A Expense Impact the Financial Statements?

The two accrual accounting concepts—depreciation and amortization—share far more commonalities than differences, as implied earlier.

The two non-cash expenses are recorded at the top of the cash flow statement (CFS) as an add-back to the accrual-based net income.

Since no real cash movement occurred in the given period, the company did not incur an actual cash outflow, which the cash flow statement reconciles with the reported cash balance.

- Income Statement ➝ On the income statement, the depreciation and amortization expense is seldom reported on a separate line item. Instead, the most common practice used by companies is to embed D&A within either the cost of goods sold (COGS) or the operating expenses section.

- Cash Flow Statement ➝ The depreciation and amortization (D&A) are indeed reported on the cash flow statement (CFS) and treated as a non-cash add-back that increases the cash flow reported in a given period. The two non-cash expenses are often consolidated for reporting purposes.

- Balance Sheet ➝ The depreciation expense reduces the carrying value of the coinciding tangible asset (PP&E), while the amortization expense reduces the carrying balance of the corresponding intangible assets.

Therefore, the recommended approach is to retrieve the separately broken-out values of the D&A expense in the footnotes section of the financial statements for purposes of performing financial analysis or building an integrated 3-statement financial model.