What is the J-Curve?

The J-Curve illustrates the timing of the receipt of proceeds by a private equity fund’s limited partners (LPs).

J-Curve in Private Equity: Growth of Fund Returns

The J-curve is a graphical representation of private equity returns, where initial losses cause a dip, followed by a reversal as the firm realizes gains on its investments.

In the private equity industry, the term “J-curve” refers to the trend line that shows the timing of a fund’s lifecycle stages relative to the proceeds received by a fund’s limited partners (LPs).

The limited partners (LPs) commit capital to the private equity firm’s fund, and the firm’s general partners (GPs) invest the capital contributed on behalf of their clients.

The net realized internal rate of return (IRR) is the compounded rate of return on an investment, which in this case refers to leveraged buyouts (LBOs).

Furthermore, the graphing of the net realized IRR creates the “J” shape pattern.

J-Curve Effect: Private Equity Fund Life Cycle Stages

The three stages of the private equity life cycle are as follows.

- Stage 1 → Investment Period (Capital Calls to Deploy into Markets)

- Stage 2 → Value Creation (Operational, Financial, and Managerial Improvements)

- Stage 3 → Harvest Period (Exits Investments to Realize Gains)

In the early stages of the fund’s lifespan – which typically lasts approximately 5 to 8+ years – the graphical representation of the cash inflows / (outflows) from the perspective of the LPs is a steep, downward slope.

The initial drop-off is attributable to the capital commitments from LPs and the annual management fee paid to the PE firm.

- Capital Commitments → The amount of capital provided by the limited partners (LPs) to the private equity firm so that the general partners (GPs) can invest and ideally earn outsized returns from their investment decisions.

- Annual Commitment Fee → The fees paid to the general partners (GPs) to cover the general operating expenses of the firm such as overhead expenses, compensation for the firm’s investment team, office supplies, and more.

Both the initial capital commitments and the management fees represent outflows of cash.

The magnitude of the outflow will reduce over time as more capital commitments occur, meaning that the fund has less capital available to call, while the management fees remain around a fixed range.

The average holding period in private equity is five to eight years, so as the fund exits its portfolio companies, the downward curve begins to reverse course and trend upward.

The curve trending upward implies the returns to the LPs are now realized.

The three most common exit strategies for private equity firms are the following:

- Sale to Strategic Acquirer

- Sale to Financial Buyer (Secondary Buyout)

- Initial Public Offering (IPO)

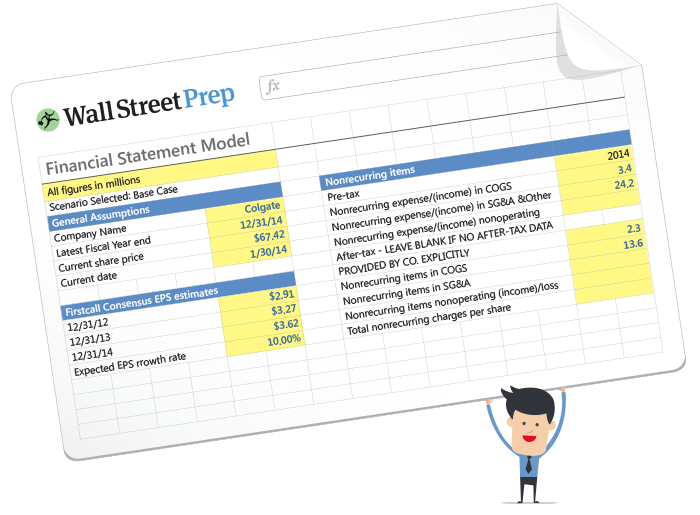

The Wharton Online and Wall Street Prep Private Equity Certificate Program

Level up your career with the world's most recognized private equity investing program. Enrollment is open for the Feb. 2026 cohort.

Enroll TodayIllustrative J-Curve Effect Graph

If the returns to a fund’s limited partners were to be graphed, the shape of the returns would be in the shape of a “J”, as the graph below depicts.

J-Curve Graph (Source: Crystal Funds)

What Factors Cause the J-Curve Shape?

- Capital Calls: In the beginning stages of the fund, once the PE firm has reached its target capital raise, the firm starts to request the capital that was committed from the LPs in order to deploy them into investments (LBOs).

- Fund Liquidity: The greater the proportion of the committed capital is allocated, the less liquid the fund is, i.e. the portfolio companies will not be sold or exited for another five to eight years.

- Investment Exits: Given more time, the firm gradually starts to exit (and realize the returns from the investment), which causes the J-curve to spiral upward, contingent on how successful the buyout panned out.

- Dry Powder: While it’ll depend on the private equity firm’s investment style and the number of investment opportunities available, the reversal occurs sooner when the fund’s investments are made earlier, rather than sitting idly as “dry powder”.

- Capital Deployment: Once most or all of the fund’s capital commitments have been deployed, the fund is no longer liquid and the firm’s focus shifts toward value creation at the portfolio company level.

- Harvest Period: In contrast, once most of the investments have been realized (i.e. the harvest period), the portfolio is now liquid, but the PE firm has effectively run out of capital to deploy.