- What is an LBO Returns Attribution Analysis?

- LBO Returns Attribution Analysis: Core Value Creation Drivers

- EBITDA Growth: Operating Improvements

- Why Does an LBO Model Calculate the Floor Valuation?

- LBO Multiple Expansion: Entry vs. Exit Multiple

- LBO Capital Structure: Debt and Equity Mix

- Add-On Acquisitions (“Roll-Ups”) and Dividend Recaps

- LBO Returns Attribution Analysis — Excel Template

- 1. LBO Returns Attribution Calculation Example

- 2. LBO Value Creation Analysis Calculation Example

- 3. LBO Returns Calculation (IRR and MoM)

What is an LBO Returns Attribution Analysis?

An LBO Returns Attribution Analysis quantifies the contribution from each of the main value creation drivers in private equity investments.

The framework for measuring the sources of value creation from a leveraged buyout (LBO) transaction is composed of three main parts:

- EBITDA Growth → Change in Initial EBITDA to Exit Year EBITDA

- Multiple Expansion → Change in Purchase Multiple to Exit Multiple

- Debt Paydown → Change in Initial Net Debt to Ending Net Debt

LBO Returns Attribution Analysis: Core Value Creation Drivers

To preface our guide on value creation analysis in LBOs, there are three main drivers of returns, which we’ll further expand upon here:

- EBITDA Growth → Growth in EBITDA can be achieved from strong revenue (“top line”) growth, as well as operational improvements that positively affect a company’s margin profile (e.g. cost-cutting, raising prices).

- Multiple Expansion → The financial sponsor, i.e. the private equity firm, seeks to exit the investment at a higher exit multiple than the purchase multiple. The exit multiple can increase from improved investor sentiment regarding a particular industry or specific trends, positive macroeconomic conditions, and favorable transaction dynamics such as a competitive auction led by strategic bidders.

- Debt Paydown → The process of deleveraging describes the incremental reduction in net debt (i.e. total debt minus cash) over the holding period. As the company’s net debt carrying balance declines, the sponsor’s equity increases in value as more debt principal is repaid using the acquired LBO target’s free cash flows (FCFs).

The main drivers of value creation in LBOs can be segmented into two distinct categories.

- Enterprise Value Improvement (TEV)

- Capital Structure (“Financial Engineering”)

The first two concepts mentioned earlier—i.e. EBITDA growth and multiple expansion—are each tied to the increase (or decrease) in the enterprise value of the post-LBO company across the holding period.

The third and final driver, the capital structure, is more related to how the LBO transaction was financed, i.e. “financial engineering”.

EBITDA Growth: Operating Improvements

EBITDA, shorthand for “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization”, is a profit metric that measures a company’s ability to efficiently generate cash flows from its core operations.

Using EBITDA as a proxy for a company’s operating cash flows tends to be the industry standard, irrespective of its shortcomings – namely because of how EBITDA is capital structure neutral and indifferent to discretionary accounting decisions.

Most acquisitions multiples are based on EBITDA (i.e. EV/EBITDA), either on a last twelve months (LTM) or next twelve months (NTM) basis.

Therefore, increasing EBITDA via revenue growth and operational enhancements directly causes the valuation of a company to rise.

Improvements in EBITDA growth can be a function of strong revenue growth year-over-year (YoY), but fixing cost inefficiencies and operational weaknesses is arguably a preferred route – albeit, both accomplish the goal of increasing EBITDA.

Fixing cost inefficiencies and operational weaknesses requires addressing internal issues, whereas revenue growth requires significant capital reinvestment, which could result in less free cash flows (FCF) to paydown debt.

Some examples of value-add opportunities to improve profit margins include:

- Reducing Employee Headcount and Shutting Down Redundant Facilities

- Eliminating Unnecessary Functions and Divesting Non-Core Assets (i.e. Shift Focus on Core Operations)

- Negotiating Longer-Term Customer Contracts

- Strategic Acquisitions to Offer Complementary Products/Services (i.e. Upselling/Cross-Selling Opportunities)

- Geographic Expansion and New End Markets

Nonetheless, companies exhibiting double-digit revenue growth (or have the potential to grow at such rates) are sold at much higher multiples than low-single-digit growth companies, which is also a crucial consideration because PE firms cannot afford to overpay for an asset.

Why Does an LBO Model Calculate the Floor Valuation?

Leveraged buyout (LBO) models are frequently referred to determining the “floor valuation” of a potential investment.

Why? The LBO model estimates the maximum entry multiple (and purchase price) that could be paid to acquire the target while still realizing a minimum IRR of, say, 20% to 25%.

Note that each firm has its own specific “hurdle rate” that must be met for an investment to be pursued.

Therefore, LBO models calculate the floor valuation of a potential investment because it determines what a financial sponsor could “afford” to pay for the target.

The Wharton Online and Wall Street Prep Private Equity Certificate Program

Level up your career with the world's most recognized private equity investing program. Enrollment is open for the upcoming cohort.

Enroll TodayLBO Multiple Expansion: Entry vs. Exit Multiple

Multiple expansion is achieved when a target company is purchased and sold on a future date at a higher exit multiple relative to the initial purchase multiple.

If a company undergoes LBO and is sold for a higher price than the initial purchase price, the investment will be more profitable for the private equity firm, i.e. “buy low, sell high”.

Once a private equity firm acquires a company, the post-LBO firm strives to pursue growth opportunities while identifying and improving upon operational inefficiencies.

Private equity investors typically do not rely on multiple expansion, however. The entry and exit multiples can fluctuate substantially, so expecting to exit at a set multiple five years from the present date can be a risky bet.

LBO Capital Structure: Debt and Equity Mix

The capital structure is arguably the most important component of a leveraged buyout (LBO).

The less equity the financial sponsor is required to contribute towards the funding of the LBO transaction, the higher the potential equity returns to the firm, so firms seek to maximize the amount of debt used to finance the LBO while balancing the debt levels to ensure that the resulting bankruptcy risk is manageable.

The capital structure is a key determinant of the success (or failure) of an LBO because the usage of debt brings substantial risk to the transaction, i.e. most of the downside risk and default risk stems from the highly levered capital structure.

The prevailing capital structures observed in the LBO markets tend to be cyclical and fluctuate depending on the financing environment, but there has been a structural shift away from the 80/20 debt-to-equity ratios in the 1980s to 60/40 splits in more recent times.

The standard LBO purchase is financed using a high percentage of borrowed funds, i.e. debt, with a relatively minor equity contribution from the sponsor to “plug” the remaining funds necessary.

Throughout the holding period, the sponsor can realize greater returns as more of the debt principal is paid down via the company’s free cash flows.

The rationale behind using more debt is that the cost of debt is lower due to:

- Higher Priority of Claim: Debt securities are placed higher up in terms of priority in the capital structure, and are far more likely to receive a full recovery in the event of bankruptcy and liquidation.

- Tax-Deductible Interest: The interest expense paid on debt outstanding is tax-deductible, which creates the so-called “tax shield”.

Therefore, the reliance on more leverage enables a private equity firm to reach its minimum returns thresholds more easily.

Add-On Acquisitions (“Roll-Ups”) and Dividend Recaps

Of course, there are more than three drivers that can impact the implied returns on an LBO.

For instance, one of the more common strategies is via add-on acquisitions, in which the portfolio company of a PE firm (i.e. the “platform company”) acquires smaller-sized companies.

But for the math to work, the add-on acquisitions must be accretive, wherein the acquirer is valued at a higher multiple compared to the acquisition target.

The increased scale and diversification from these consolidation plays can contribute to more stable, predictable cash flows, which are two traits that private equity investors place substantial weight on.

Add-ons can provide numerous benefits to the platform company, such as improved branding, pricing power, and risk mitigating factors like revenue diversification, but also increase the odds of exiting at a higher multiple than at entry, i.e. multiple expansion.

Another method to improve LBO returns is via a dividend recapitalization (“recap”), which occurs when a financial sponsor raises more debt with the sole purpose of issuing shareholders a one-time dividend.

Dividend recaps are performed to monetize profits from the LBO prior to a complete exit, and the timing of the recap has the additional benefit of increasing the fund’s IRR since the proceeds are received earlier.

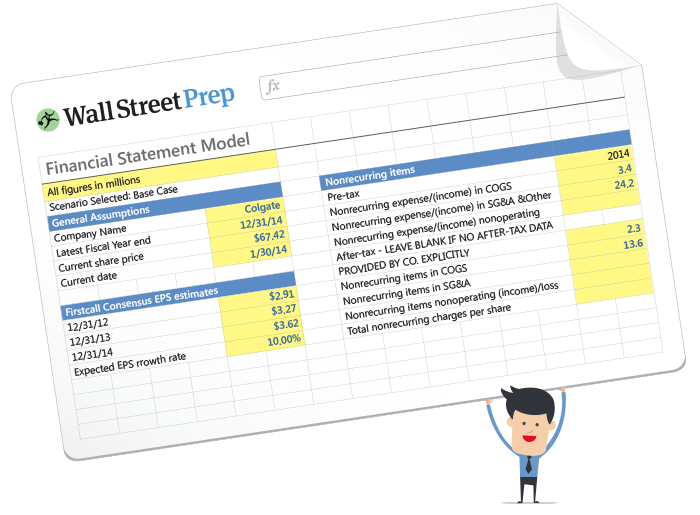

LBO Returns Attribution Analysis — Excel Template

We’ll now move on to a modeling exercise, which you can access by filling out the form below.

1. LBO Returns Attribution Calculation Example

Suppose a financial sponsor completed the LBO of a target company with an LTM EBITDA of $50 million, which will expand at a constant growth rate of 5% throughout the entire five-year time horizon.

- LTM EBITDA (Year 0) = $50 million

- EBITDA Growth Rate = 5.0%

If we apply the 5% growth rate to our LTM EBITDA, we arrive at the following figures for projected EBITDA.

- EBITDA (Year 1) = $53 million

- EBITDA (Year 2) = $55 million

- EBITDA (Year 3) = $58 million

- EBITDA (Year 4) = $61 million

- EBITDA (Year 5) = $64 million

The purchase multiple was 10.0x LTM EBITDA and the initial leverage multiple was 6.0x.

- LTM Multiple = $50 million

- Purchase Multiple = 10.0x

- Initial Leverage Multiple (Net Debt / EBITDA) = 6.0x

- Fees = 4.0% of TEV

Using those assumptions, we can calculate the purchase enterprise value (TEV) as $500 million by multiplying the LTM multiple by the LTM EBITDA.

We can also calculate net debt in Year 0 by multiplying the initial leverage multiple by the LTM EBITDA.

- Purchase Enterprise Value = 10.0x × $50 million = $500 million

- Net Debt (Year 0) = 6.0x × 50 million = $300 million

In Year 1, the net debt paydown is 15%, so the percentage of remaining net debt is 85%.

- % Original Net Debt (Year 1) = 85%

From that point onward, we’ll assume the net debt paydown is 20% until the financial sponsor exits the investment at the end of Year 5.

- Net Debt Paydown = –20% Per Year

Given that assumption, the percentage of original net debt reduces from 85% in Year 1 to 5% in Year 5, the exit year.

- % Original Net Debt (Year 2) = 65%

- % Original Net Debt (Year 3) = 45%

- % Original Net Debt (Year 4) = 25%

- % Original Net Debt (Year 5) = 5%

By the time the sponsor exits its investment, the target was able to pay down 95% of its initial net debt—or to quantify the repaymet of debt, the debt balance declined from $300 million to $15 million over the 5-year holding period.

2. LBO Value Creation Analysis Calculation Example

While it is the standard convention for the exit multiple to be conservatively set equal to the purchase multiple, we’ll assume in this case that the exit multiple is 12.0x and then multiply it by the LTM EBITDA in Year 5 to arrive at the exit enterprise value.

- Exit Multiple = 12.0x

- Exit Enterprise Value = 12.0x × $64 million = $766 million

We now have all the necessary inputs for our value creation analysis.

The first step is to calculate the entry valuation by subtracting the initial net debt and adding the fees (i.e. transaction and financing fees) to the purchase enterprise value.

- Purchase Enterprise Value = $500 million – $300 million + 20 million = $220 million

In the second step, we’ll calculate the exit valuation by subtracting the exit year net debt from the exit enterprise value and subtracting fees.

- Exit Enterprise Value = $766 million – $15 million – $31 million

The fees are added to the purchase enterprise value but subtracted from the exit enterprise value because the fees should cause the required initial equity contribution to increase.

However, the exit enterprise value is “net” of fees, so the proceeds received should be reduced by the transaction and financing fees that need to be paid at exit.

In the final step, we’ll calculate the value contribution from each driver using the following formulas:

- EBITDA Growth = (Exit Year EBITDA – Initial EBITDA) × Purchase Multiple

-

- EBITDA Growth = ($64 million – $50 million) × 10.0x = $138 million

-

- Multiple Expansion = (Exit Multiple – Purchase Multiple) × Exit Year LTM EBITDA

-

- Multiple Expansion = (12.0x – 10.0x) × $64 million = $128 million

-

- Debt Paydown = Initial Net Debt – Exit Year Net Debt

-

- Debt Paydown = $300 million – $15 million = $285 million

-

- Fees = (Exit Year Fees) – (Entry Fees)

-

- Fees = ($31 million) – ($20 million) = $51 million

-

The total value creation comes out to $500 million, which is equal to the difference between the sponsor’s initial equity ($220 million) and the sponsor’s exit equity ($720 million).

- Total Value Creation = $138 million + $128 million + $285 million – $51 million = $500 million

The following percentages reflect which variables were the most impactful on returns.

- EBITDA Growth = 27.6%

- Multiple Expansion = 25.5%

- Debt Paydown = 57.0%

- Fees = –10.1%

3. LBO Returns Calculation (IRR and MoM)

If we divide the sponsor’s exit equity by the sponsor’s initial equity, we can calculate the multiple-of-money (MoM), which comes out to 3.27x.

- Multiple of Money (MoM) = $720 million ÷ $220 million = 3.27x

The IRR can be estimated by raising the multiple-of-money (MoM) to the power of (1 ÷ t) and subtracting the result by one.

In closing, the implied IRR of the LBO investment is 26.76%.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) = 3.27x ^ (1 ÷ 5) – 1 = 26.76%

Hi! just to clarify, why EBITDA growth impact is calculated multiplying the difference in EBITDAs with the Purchase EBITDA Multiple, whereas multiple expansion multiplying the difference in multiples with the Exit Year EBITDA? I understand why we use the difference in both cases, I just don’t get why in one… Read more »

Hi, Kate, We use the purchase multiple for EBITDA growth impact because we assume the exit multiple is the same as purchase multiple in order to isolate the impact of EBITDA growth assuming no change in multiple from the change in value in the actual multiple itself, which we attribute… Read more »