- How Does a Rolling Forecast Work?

- Why Do Organizations Need a Rolling Forecast?

- Budgeting and Planning Process: Key Steps

- Rolling Forecast vs. Traditional Budget: What is the Difference?

- What are the Best Practices to Build a Rolling Forecast?

- Ready to Roll? Be Prepared for a Cultural Shift

- Conclusion to FP&A Rolling Forecast Guide

How Does a Rolling Forecast Work?

A rolling forecast is a management tool that enables organizations to continuously plan (i.e. forecast) over a set time horizon.

For example, if your company produces a plan for calendar year 2018, a rolling forecast will re-forecast the next twelve months (NTM) at the end of each quarter.

This differs from the traditional approach of a static annual forecast that only creates new forecasts towards the end of the year:

From the screenshot above, you can see how the rolling forecast approach is a continuous rolling 12-month forecast, while the forecast window in the traditional, static approach will continue to shrink the closer it gets to year end (“the fiscal year cliff”). When used appropriately, a rolling forecast is an important management tool that allows companies to see trends or potential headwinds and adjust accordingly.

Why Do Organizations Need a Rolling Forecast?

The purpose of this article is to shed light on rolling forecast best practices for mid-sized and larger organizations, but let’s start with the absolute basics.

Imagine you start a freelance consulting company. You run your sales by cold calling prospects, you run the marketing by building a website and you run payroll and manage all expenses. At this stage, its just you.

The “keep-it-in-owner’s-head” approach stops working when a few employees are added to the company. A complete view of the business becomes challenging to maintain.

Naturally, you have a great handle on all aspects of your business because you’re at the ground floor for everything: You’re talking to all prospective clients, you’re running all the actual consulting projects and you’re generating all the expenses.

This knowledge is critical because you need to know how much money you can afford to invest in the business to grow it. And if things go better (or worse) than expected, you’ll know what happened (i.e. one of your clients didn’t pay, your website expenses got out of control, etc).

The problem is that the “keep-it-in-owner’s-head” approach stops working when a few employees are added to the company. As departments grow and the company creates new divisions, a complete view of the business becomes challenging to maintain.

For example, the sales team might have a great sense of the revenue pipeline but no insight into expenses or working capital issues. As such, a common issue for growing companies is that management’s decision-making ability degrades until it implements a process for regaining a full view of what’s going on. This view is needed to gauge the health of distinct parts of the business and is critical in making decisions on how to most effectively invest capital. For companies with multiple divisions, the challenge of gathering a complete view is even more acute.

The Wharton Online and Wall Street Prep Financial Planning & Analysis (FP&A) Certificate Program

Elevate your finance career with Wharton's globally recognized FP&A Certificate Program. Enrollment is open for the Feb. 2026 cohort.

Enroll TodayBudgeting and Planning Process: Key Steps

As a response to the challenges described above, most companies manage corporate performance through a budgeting and planning process.

This process produces a standard of performance by which sales, operations, shared service areas, etc., are measured. It follows the following sequence:

- Create a forecast with specific performance targets (revenue, expenses).

- Track actual performance against targets (budget to actual variance analysis).

- Analyze and course correct.

Rolling Forecast vs. Traditional Budget: What is the Difference?

Criticism of Traditional Budget

The traditional budget is usually a one-year forecast of revenue and expenses down to net income. It is built from the “bottom up,” which means that individual business units supply their own forecasts for revenue and expenses, and those forecasts are consolidated with corporate overhead, financing and capital allocations to create a full picture.

The static budget is the pen-to-paper filling out of the next year in a company’s strategic plan, usually a 3-5 year view of where management wants consolidated revenue and net income to be, and which products and services should drive growth and investment over the coming years. To use a military analogy, think of the strategic plan as strategy produced by the generals, while the budget is the tactical plan commanders and lieutenants use to execute the generals’ strategy. So…back to the budget.

Broadly speaking, the purpose of a budget is to:

- Clarify resource allocation (How much should we spend on advertising? Which departments require more hiring? Which areas should we invest more into?).

- Provide feedback for strategic decisions (Based on how poorly our sales of products from Division X are expected to perform, should we divest that division?)

However, there are several areas where the traditional budget falls short. The biggest criticisms of the budget are as follows

Criticism 1: The traditional budget does not react to what is actually happening in the business during the forecast.

The traditional budget process can take up to 6 months at large organizations, which requires business units to guess about their performance and budget requirements up to 18 months in advance. Thus, the budget is stale almost as soon as it’s released and becomes more so with each passing month.

For example, if the economic environment changes materially three months into the budget, or if a major customer is lost, resources allocations and targets will need to shift. Since the annual budget is static, it is a less-than-useful tool for resource allocation and a poor tool for strategic decision making.

Criticism 2: The traditional budget creates a variety of perverse incentives at the business-unit level (sandbagging).

A sales manager is incentivized to provide overly conservative sales forecasts if he or she knows the forecasts will be used as a target (better to under promise and over deliver). These kinds of biases reduce the accuracy of the forecast, which management needs in order to get an accurate picture of how the business is expected to fare.

Another budget-created distortion has to do with the budget request timeline. Business units provide requests for budgets based on expectations of far-into-the-future performance. Managers who don’t use all of their allocated budget will be tempted to use up the excess to ensure that their business unit gets the same allocation the next year.

Benefits of Rolling Forecast Model

The rolling forecast strives to address some of the shortcomings of the traditional budget. Specifically, the rolling forecast involves a re-calibration of forecasts and resource allocation every month or quarter based on what’s actually happening in the business.

Adoption of rolling forecasts is far from universal: An EPM Channel survey found at only 42% of companies use a rolling forecast.

Making resource decisions as close to real time as possible can funnel resources more efficiently to where they’re needed most. It provides managers with a timely vision into the next twelve months at any given point in the year. Lastly, a more frequent, reality-tested approach to target setting keeps everyone more honest.

Challenges of Rolling Forecasts

For the reasons above, it may seem like a no-brainer to power-charge a budget with a regularly updating rolling forecast. And still, adoption of rolling forecasts is far from universal: An EPM Channel survey found at only 42% of companies use a rolling forecast.

While a few firms have completely eliminated the static annual budget process in favor or a continuous rolling forecast, a large portion of those adopting a rolling forecast are using it alongside, not instead of, a traditional static budget. That’s because the traditional annual budget is still considered by many organizations to provide a useful guidepost connected to a long term strategic plan.

The primary challenge with a rolling forecast is implementation. In fact, 20% of companies polled indicated that they tried the rolling forecast but failed. This shouldn’t be entirely surprising — the rolling forecast is harder to implement than a static budget. The rolling forecast is a feedback loop, changing constantly based on real time data. That’s much harder to manage than a static output in a traditional budget.

In the sections below, we outline some of the best practices that have emerged around the execution of a rolling forecast as a guide for companies making the transition.

What are the Best Practices to Build a Rolling Forecast?

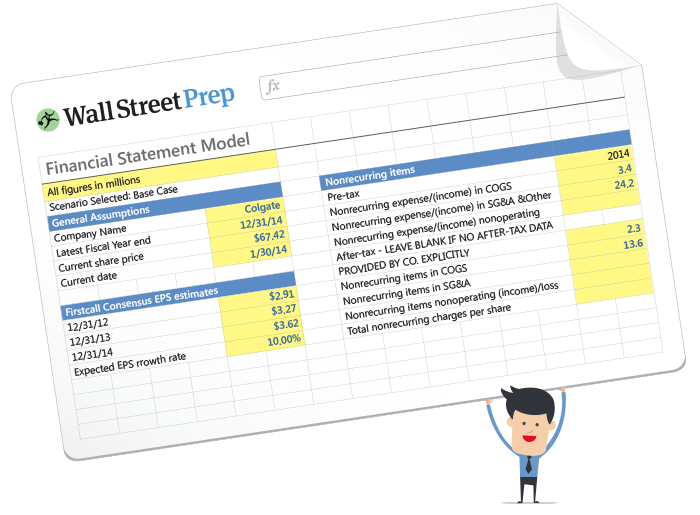

Rolling Forecast in Excel

Excel remains the day-to-day workhorse in most finance teams. For larger organizations, the traditional budget process usually involves building the forecast in Excel before loading them into an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system.

Without a lot of initial labor and setup, the rolling forecast process can be fraught with inefficiencies, miscommunication and manual touch points.

As new data comes in, not only do firms need to perform a budget to actuals variance analysis, but they also need to re-forecast future periods. This is a tall order for Excel, which can quickly become unwieldy, error prone, and less transparent.

That’s why a rolling forecast requires an even more carefully constructed relationship between Excel and the data warehouses/reporting systems than that of a traditional budget process. As it already stands, according to FTI Consulting, two out of every three hours of an FP&A analyst’s day are spent searching for data.

Without a lot of initial labor and setup, the rolling forecast process can be fraught with inefficiencies, miscommunication and manual touch points. A generally recognized requirement in the transition to a rolling forecast is the adoption of a Corporate Performance Management (CPM) system.

Determine the Forecast Time Horizon

Should your rolling forecast roll monthly? Weekly? Or should you use a 12- or 24-month rolling forecast? The answer depends on a company’s sensitivity to market conditions as well as its business cycle. All else being equal, the more dynamic and market dependent your company, the more frequent and shorter your time horizon needs to be to react effectively to changes.

Meanwhile, the longer your company’s business cycle is, the longer your forecast ought to be. For example, if capital investment in equipment is expected to begin making an impact after 12 months, the roll needs to extend to reflect the impact of that capital investment. Larysa Melnychuk of FPA Trends provided the following industry examples in a presentation at the AFP annual conference:

| Industry | Time horizon |

|---|---|

| Airline | Rolling 6 quarters, monthly |

| Technology | Rolling 8 quarters, quarterly |

| Pharmaceutical | Rolling 10 quarters, quarterly |

Naturally, the longer the time horizon, the more subjectivity required and the less precise a forecast. Most organizations can forecast with a relative degree of certainty over a 1- to 3-month time period, but beyond 3-months the fog of business significantly increases and forecast accuracy begins to wane. With so many moving parts in the internal and external environment, organizations must rely upon finance to spin the gold of foresight and provide probabilistic estimates of the future instead of bullseye targets.

Roll with Drivers, not with Revenue

When forecasting, it is generally preferable to break down revenue and expenses into drivers whenever possible. In plain english, this means that if you are charged with forecasting Apple’s iPhone sales, your model should explicitly forecast iPhone units and iPhone cost per unit rather than an aggregate revenue forecast such as “iPhone revenue will grow 5%.”

See a simple example of the difference below. You can get the same result both ways, but the driver-based approach enables you to flex assumptions with more granularity. For example, when it turns out you didn’t achieve your iPhone forecast, the driver-based approach will tell you why you missed it: Did you sell fewer units or was it was because you had to discount too heavily?

Along with a variety of financial modeling best practices, drivers should be leveraged in a planning model. They are the predictor variable in the economic equation. It may not be feasible to have drivers for all general ledger line items. For these, trending against historical norms may make the most sense.

Drivers can be seen as the “joints” in a forecast — they allow it to flex and move as new conditions and restraints are introduced. In addition, driver-based forecasting may require fewer inputs than traditional forecasting and can help to automate and shorten planning cycles.

Variance Analysis

How good is your rolling forecast? Prior-period forecasts should always be compared against actual results over time.

Below you see an example of a actual results (the shaded actuals column) compared against both the forecast, the prior month, and the prior year’s month. This process is called a variance analysis and is a key best practice in financial planning and analysis. A variance analysis is also a key followup on the traditional budget, and is called a budget-to-actual variance analysis.

The reason for comparing actuals to prior periods as well as budgets and forecasts is to shed light on the effectiveness and accuracy of the planning process.

Ready to Roll? Be Prepared for a Cultural Shift

Organizations are structured around the budgeting, forecasting, planning and reporting cycles that currently exist. Fundamentally changing the expected output of that structure and how employees interact with the forecast is a steep challenge.

Below are four areas to focus on when implementing a rolling forecast process:

1. Garner Participation

Perform an assessment of the current forecast process that identifies where major data hand-offs are as well as when and to who forecast assumptions are made. Map out the new rolling forecast process identifying the information that will be needed and when it will be needed, then communicate it.

Too much emphasis cannot be placed on communicating these changes. Many organizations have gone generations relying upon an annual budget performed once a year and have dedicating significant time and energy to its completion.

A rolling forecast process will require shorter, more frequent blocks of time focused throughout the year. Communicating changes and managing expectations is critical to a rolling forecast success.

2. Change Behavior

What are the greatest flaws of your current forecasting system and how can that behavior be changed? For example, if budgeting is only done once a year and that is the only time a manager can request funding, then sandbagging and underestimating will ensue as a natural tendency to protect one’s territory. When asked to forecast more frequently and further out, those same tendencies may linger.

The only way to change behavior is with senior management buy-in. Management must be committed to the change and believe that more accurate, further-out forecasts will lead to better decision making and higher returns.

Reinforce to line managers that changing numbers to best reflect real conditions is in their best interest. Everyone should be asking themselves, “What new information has become available since the last forecast period that changes my view of the future?”

3. De-Couple the Forecast from the Reward

Forecast accuracy decreases when performance rewards are tied to the outcomes. Setting targets based on a forecast will lead to greater forecast variance and less useful information. An organization should have a periodic planning process in which targets are set for managers to achieve. Those targets should not change based on the most recent forecast. This would be like moving the goal posts after the game starts. It’s also a morale killer if it’s done as targets come closer to being reached.

4. Senior Management Education

Senior managers should make every effort to encourage participation in the rolling forecast process by explaining how it allows the organization to adapt to changing business conditions, capture new opportunities and avoid potential risks. Most importantly, they should focus on how doing each of these things will increase participants’ potential reward.

Conclusion to FP&A Rolling Forecast Guide

As businesses continue to grow into more dynamic and larger versions of themselves, forecasting will get increasingly harder, whether because of an increase in line items or because of the growing amount of information needed to build the forecast model. Nevertheless, by following the best practices outlined above when implementing a rolling forecast process, your organization will be better prepared for success.

When calculating driver based forecasting, you mentioned that the cost per unit and i iphone units should be calculated. But you your example shows with (price * units). Shouldn

t be used withcost per unit * unitsrather thanprice* units? Because it gives ussales revenue` ?Many thanks

Dilara:

In this article, the cost per unit is the cost to the consumer, i.e., the sales price.

Best,

Jeff

When completing variance to forecast, if you are forecasting monthly or quarterly, which forecast is the basis for the variance to actuals? I feel that if you use the most recent forecast, that diminishes the variance and usability of the variance analysis. But if you use the original forecast, why… Read more »

Scott: I personally think it would be useful to do both, as per one of the points in the article. Use both a rolling forecast to predict near-term results and make more timely adjustments while also using the traditional method for longer term planning (the traditional method would of course… Read more »