What is Treasury Stock?

Treasury Stock represents shares that were issued and traded in the open markets but are later reacquired by the company to decrease the number of shares in public circulation.

Treasury Stock Balance Sheet Accounting

On the shareholders’ equity section of the balance sheet, the “Treasury Stock” line item refers to shares that were issued in the past but were later repurchased by the company in a share buyback.

Following the repurchase, the formerly outstanding shares are no longer available to be traded in the markets and the number of shares outstanding decreases – i.e. the reduced number of shares publicly traded is referred to as a decline in the “float”.

Since the shares are no longer outstanding, there are three notable impacts:

- The repurchased shares are NOT included in the calculation of basic or diluted earnings per share (EPS).

- The repurchased shares are NOT included in the distribution of dividends to equity shareholders.

- The repurchased shares do NOT retain the voting rights previously given to the shareholder.

Therefore, an increase in treasury stock via a share buyback program or a one-time buyback can cause the share price of a company to “artificially” increase.

The value attributable to each share has increased on paper, but the root cause is the decreased number of total shares, as opposed to “real” value creation for shareholders.

Share Buyback Rationale and Impact on Share Price

The rationale for share repurchases is often that management has determined its share price is currently undervalued. Share repurchases – at least in theory – should also occur when management believes its company’s shares are underpriced by the market.

If the company’s share price has fallen in recent periods and management proceeds with a buyback, doing so can send out a positive signal to the market that the shares are potentially undervalued.

In effect, the company’s excess cash sitting on its balance sheet is utilized to return some capital to equity shareholders, rather than issuing a dividend.

If the shares are priced correctly, the repurchase should not have a material impact on the share price – the actual share price impact comes down to how the market perceives the repurchase itself.

Controlling-Stake Retention

One common reason behind a share repurchase is for existing shareholders to retain greater control of the company.

By increasing the value of the shareholders’ interest in the company (and voting rights), the repurchase of shares helps fend off hostile takeover attempts.

If the equity ownership of a company is more concentrated, takeover attempts become far more challenging (i.e. certain shareholders hold more voting power), so share buybacks can also be utilized as a defensive tactic by management and existing investors.

Treasury Stock Contra-Equity Journal Entry

Why is Treasury Stock Negative?

Treasury stock is considered a contra-equity account.

Contra-equity accounts have a debit balance and reduce the total amount of equity owned – i.e. an increase in treasury stock causes the shareholders’ equity value to decline.

That said, treasury stock is shown as a negative value on the balance sheet and additional repurchases cause the figure to decrease further.

On the cash flow statement, the share repurchase is reflected as a cash outflow (“use” of cash).

After a repurchase, the journal entries are a debit to treasury stock and credit to the cash account.

If the company were to resell the previously retired shares at a higher price than the original price (i.e. when retired), the cash would be debited by the sale amount, treasury stock would be credited by the original amount (i.e. same as prior), but the additional paid in capital (APIC) account would be credited to ensure both sides balance.

If the board elects to retire the shares, the common stock and APIC would be debited, while the treasury stock account would be credited.

Treasury Stock in Diluted Share Count Calculation

To calculate the fully diluted number of shares outstanding, the standard approach is the treasury stock method (TSM).

Examples of Potentially Dilutive Securities

- Options

- Employee Stock Options

- Warrants

- Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

Under the TSM, the options currently “in-the-money” (i.e. profitable to exercise as the strike price is greater than the current share price) are assumed to be exercised by the holders.

However, the more prevalent treatment in practice has been for all outstanding options – regardless of if they are in or out of the money – to be included in the calculation.

The intuition is that all outstanding options, despite being unvested on the present date, will eventually be in the money, so as a conservative measure, they should all be included in the diluted share count.

The final assumption of the TSM approach is that the proceeds from the exercise of the dilutive securities will immediately be used to repurchase shares at the current share price – under the presumption that the company is incentivized to minimize the net impact of dilution.

Retired vs. Non-Retired Treasury Stock

Treasury stock can either be in the form of:

- Retired Treasury Stock (or)

- Non-Retired Treasury Stock

Retired treasury stock – as implied by the name – is permanently retired and cannot be re-instated on a later date.

In comparison, non-retired treasury stock is held by the company for the time being, with the optionality to be re-issued at a later date if deemed appropriate.

For example, non-retired shares can be re-issued and ultimately return to being traded in the open markets by:

- Dividends to Equity Shareholders

- Shares Issued Per Options Agreements (and Related Securities – e.g. Convertible Debt)

- Stock-Based Compensation for Employees

- Capital Raising – i.e. Secondary Offerings, New Financing Round

Treasury Stock Cost Method vs. Par Value Method

In general, there are two methods of accounting for treasury stock:

- Cost Method

- Par Value Method

Under the cost method, the more common approach, the repurchase of shares is recorded by debiting the treasury stock account by the cost of purchase.

Here, the cost method neglects the par value of the shares, as well as the amount received from investors when the shares were originally issued.

By contrast, under the par value method, share buybacks are recorded by debiting the treasury stock account by the shares’ total par value.

The cash account is credited for the amount paid to purchase the treasury stock.

In addition, the applicable additional paid-in capital (APIC) or the reverse (i.e. discount on capital) must be offset by a credit or debit.

- If the credit side is less than the debit side, APIC is credited to close the difference

- If the credit side is greater than the debit side, APIC is debited instead.

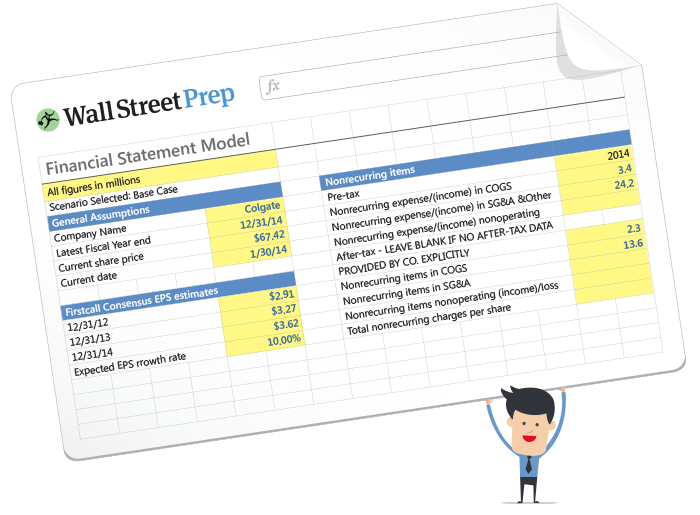

Everything You Need To Master Financial Modeling

Enroll in The Premium Package: Learn Financial Statement Modeling, DCF, M&A, LBO and Comps. The same training program used at top investment banks.

Enroll Today

hello im CPA student would like to know what is the JV when when the treasury stocks will be sold or retired with an amount less or more of the original issuance price appreciate if you will answer through an example. thanks much appreciated

Hi, Qussay,

If a share was repurchased at $10 and reissued at $20, then at the time of reissuance, $20 debit to cash, $10 credit (decrease) to treasury stock, and $10 credit to APIC.

BB