What is Value investing?

Value investing is a type of investing that focuses on identifying stocks that are underpriced relative to their true (intrinsic) value. Value investing is therefore typically associated with contrarian investing and identifying industries and businesses that have fallen out-of-favor with growth-oriented investors.

- Value investing seeks stocks priced below intrinsic value, emphasizing discounted cash flow and fundamental analysis.

- It involves a contrarian approach, targeting undervalued sectors like financials, consumer durables, and legacy media.

- A margin of safety ensures investments are made only when market prices significantly undercut intrinsic value estimates.

- Long-term focus allows markets to correct mispricing, rewarding disciplined and patient investors.

- Leaders like Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett exemplify the strategy’s principles and enduring relevance.

Introduction to Value Investing

Warren Buffett, the most famous value investor of all time, once famously said “Price is what you pay, value is what you get.”

Understanding that crucial distinction lies at the heart of value investing, a type of investing that focuses on identifying stocks (i.e. “equities”) that are priced below their fundamental value (also called intrinsic value).

The Greatest Value Investment of All Time

In 2016, Buffett, who typically avoids tech stocks, began to view Apple as undervalued. Apple was trading at $30 per share, with a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of merely 10.6x, far lower than other tech companies as growth-oriented investors (see below) began to question Apple’s ability to grow.

At 10.6x Buffett, did not need to believe that Apple’s revenue will grow fast to gain conviction on the trade.

Instead, Buffett saw Apple’s moats – created from its product ecosystems and App store and brand loyalty – as well as high profit margins, and consistent cash flows as a highly attractive value investment.

Starting in Q1 2016, Buffett began purchasing Apple shares, and kept acquiring until Berkshire’s holdings peaked at 900 million shares in 2023.

During that time, Apple’s earnings have doubled, but its share price grew 800%, significantly outpacing the earnings growth.

As of December 9, 2024, Apple shares traded at $246.75, at a 40.0x price-to-earnings ratio. With such a high PE ratio, Berkshire began reducing its holdings. As of Q3 2024, the Company holds only 300 million Apple shares.

Source: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AAPL/apple/pe-ratio

Intrinsic Value

Of course, value investing isn’t as simple as identifying low-multiple businesses. Correctly priced businesses also trade at low-multiples if they are fundamentally bad businesses.

Value investors don’t just look for businesses that are priced low, they look for businesses that are priced too low.

The crux, then, of value investing is to identify low-multiple companies whose intrinsic value is substantially above the share price. But while stock price is observable in the stock market, the intrinsic value of a company is much harder to estimate.

A company’s intrinsic value represents an investor’s best estimation of the present value of the free cash flows the underlying business will generate in the future. Intrinsic value is the foundation of value investing.

At its core, intrinsic value of a business is a function of the cash flows that it can generate in the future, discounted to the present using a cost of capital that accurately reflects the riskiness and uncertainty of achieving those cash flows.

To estimate a company’s potential future cash flows, investors must perform fundamental analysis, which involves: evaluating the business operations, competitive advantages, growth opportunities, and the various risks to the business.

Fundamental Analysis

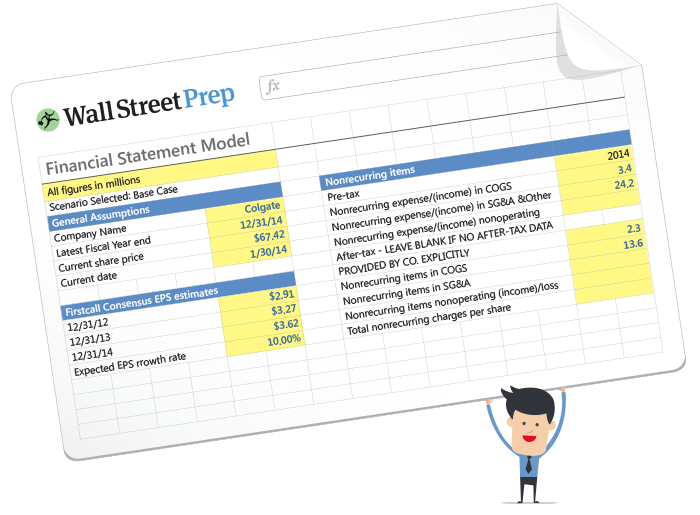

So how is this actually done in real life by investors? Real-world value investors spend A LOT of time digging through company filings, poring over 10Ks, 10Qs, management conference call transcripts and press releases.

This research provides insights for value investors across a variety of key aspects of the business:

Financial Statement Analysis

Qualitative Business Assessment

- Market and Industry Dynamics

- Competitive Advantages / Barrier to Entry

- Cyclicality

- Management Quality

Drivers of Value

The Wharton Online & Wall Street Prep Applied Value Investing Certificate Program

Learn how institutional investors identify high-potential undervalued stocks. Enrollment is open for the Feb. 2026 cohort.

Enroll TodayIndustries Favored by Value Investors

Industries favored by value investors, tend to be the kinds of industries that don’t enjoy a lot of growth, and therefore attention from more growth-orientated investors. As Bill Nygren, legendary value investor at Oakmark put it during an interview with Barron’s:

When you look at our portfolio, you don’t see the mega tech. Instead, you see mundane traditional businesses like General Motors and Citigroup that are trading at single-digit P/E multiples, returning a lot of capital to shareholders.

Even though those businesses aren’t as exciting as the names that have been leading the S&P 500, investor returns might be higher because of how much capital they can return to shareholders and how low the starting P/E ratios are.

One of the interesting things about the market is that there are lots of industries where you can find decent, large businesses that are trading at less than half the market multiple. You see it a lot in the financials, especially banking and insurance, but it’s also in consumer durables, like the auto industry. It’s in legacy media, even some of the healthcare names that haven’t kept up with the market over the past couple of years are available at barely double-digit P/E ratios.

Risk and Margin of Safety

Risk is a crucial component of assessing intrinsic value – two companies can share the same expectation for cash flows. But if one of those businesses faces significantly lower risks to achieving those cash flows, the value of that business could be significantly higher than the alternative.

Risk comes from a variety of places.

The gap between the intrinsic value a value investor estimates and the market price is the margin of safety.

The basic idea is value investors should allow for a margin of safety between their intrinsic value estimate and the market price to account for market volatility, the imperfection of valuation methods, and to protect against adverse events or other miscalculations. A rule of thumb is that value investors should embed a 20-50% discount to their intrinsic valuation when evaluating the margin of safety.

Margin of Safety – Simple Example

A value investor estimates a company offers an $100 per share intrinsic value, the investor should apply a discount to that value – say 30% – to apply a margin of safety. This of course, drops the post-margin of safety intrinsic value per share to $70 per share.

If the trading price is below the $70, it remains an attractive value investment. However, if the trading price is above $70 per share – say $90 per share – it is no longer an attractive investment for a value investor, even though the undiscounted intrinsic value is higher at $100 per share.

This is meant to impose investor discipline and obviously raises the bar for making investments. Seth Klarman, legendary value investor and founder of Baupost wrote an important (but also ridiculously expensive) book on this, aptly called Margin of Safety

Long Term Investment Horizon

Another tenet of value investing is that markets may misprice stocks in the short term, but over the long run, markets correct themselves and reward disciplined investors, notwithstanding John Maynard Keynes’ famous warning that “over the long run, we are all dead.”

In Warren Buffett’s 2023 Letter to Shareholders, he explained his long term view and how Berkshire Hathaway exploits short term mispricing.

Occasionally, markets and/or the economy will cause stocks and bonds of some large and fundamentally good businesses to be strikingly mispriced. Indeed, markets can – and will – unpredictably seize up or even vanish as they did for four months in 1914 and for a few days in 2001. If you believe that American investors are now more stable than in the past, think back to September 2008. Speed of communication and the wonders of technology facilitate instant worldwide paralysis, and we have come a long way since smoke signals. Such instant panics won’t happen often – but they will happen.

Berkshire’s ability to immediately respond to market seizures with both huge sums and certainty of performance may offer us an occasional large-scale opportunity. Though the stock market is massively larger than it was in our early years, today’s active participants are neither more emotionally stable nor better taught than when I was in school. For whatever reasons, markets now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young. The casino now resides in many homes and daily tempts the occupants.

Value Investing versus Growth Investing

Value investing is one of the prominent active investing strategies that rely heavily on fundamental analysis. The other is Growth Investing.

Whereas value investing involves identifying and investing in companies whose stocks are trading below their intrinsic or true value, growth investors focus, as the name suggests, on companies that have potential for high growth.

While value investing and growth investing strategies both require a deep understanding of a company’s fundamentals and involve detailed fundamental analyses, they cater to different investment philosophies: value investing seeks contrarian, undervalued opportunities for long-term gains, while growth investing aims to capitalize on companies with high growth potential.

Here are the key differences between the growth investing and value investing strategies:

| Growth Investing | Value Investing | |

|---|---|---|

| Investment philosophy | Invest in businesses expected to grow significantly faster than the market. Willing to pay a premium for potential. | Identify undervalued businesses trading below intrinsic value. Seeking bargains, looking at out of favor industries and businesses. |

| Fundamental analysis focus | Revenue growth, earnings growth, TAM analysis, market share expansion. | Returns on invested capital, Price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-book (P/B), dividend yield. |

| Risk Tolerance | Higher as more value is dependent on growth in the future. | Lower risk, focus on steady cash flows, solid businesses with defensible moats. |

| Investment Horizon | Long-term | Long-term |

| Typical Industries | Tech, biotech, e-commerce, innovative startups. | Consumer staples, utilities, mature industries. |

| Market Conditions | Performs well in bullish markets or during economic expansion. | Performs well in bearish or uncertain markets as investors seek safety. |

| Risk Factors | High valuation risk, susceptible to market corrections. | Risk of prolonged underperformance if undervaluation persists. |

| Illustrative Investments | Tesla, Amazon, Doordash | Coca-Cola, Citigroup, or Starbucks |

How to Screen for Value Investments

So how do value investors begin when looking for opportunities?

As a good starting point, there are screening tools that help you screen for public companies, by filtering things like maximum PE ratios, industries, market cap, and other attributes.

- Morningstar

- Bloomberg Terminal or FactSet: (institutional-grade platforms)

- Yahoo Finance

- Finviz

Morningstar Screen

While these screening tools are very helpful, what you actually screen for is an important first step. There are a variety of attributes to screen for on the value investing checklist:

- Industry / Sector

- Market capitalization

- Price-to-earnings ratio

- Price-to-book ratio

- Liquidity ratios

- Earnings growth

- Debt and leverage ratios

Note that these are not exhaustive. In addition, many investors have benchmarks (i.e. “I look for businesses below a PE of 10.0x”) and depending on the investor style or preferences, some of these might be “nice to haves” as opposed to “must haves.”

Value Investing Track Record and Performance

Value investing is a long-term investment strategy, and has outperformed the overall stock market all but three times on any rolling 10-year period in the last 90 years – the Great Depression, the Technology Bubble, and, most notably, ever since the Global Financial Crisis.

As was the case in the run up to the tech bubble of the late 1990s, the last decade has been particularly challenging for value investing: The Russell 1000 Growth Index has returned investors 350% compared to 120% for the Russell 1000 Value Index, for the 10 years ending June 30, 2024.

Source: Dodge & Cox, Kenneth French’s Data Library

Is Value Investing Dead?

Nonetheless, many investors view the recent history of underperformance as a temporary consequence of historically low interest rates, rapid technological advancements, unprecedented stimulus by Central Banks, and shifting investor preferences. Many value investors believe history will vindicate value investing and that value’s potential for future returns remains great.

Notable Value Investors

-

Benjamin Graham – Founding Father of Value Investing

Benjamin Graham – Warren Buffett’s mentor and founding father of value investing – introduced the concept of intrinsic value and wrote two bibles of investing – The Intelligent Investor and Security Analysis.

Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger – CEO and Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, respectively. Buffett is considered the beset investor of all time and his letters to shareholders are considered a must read for any value investor.

Other notable value investors include:

- Seth Klarman – Founder of Baupost Group

- Howard Marks – Co-founder of Oaktree Capital

- John Templeton – Contrarian investor, founder of Templeton Growth Fund

- Peter Lynch – Former manager of the Fidelity Magellan Fund

- Joel Greenblatt – Founder of Gotham Capital and author of The Little Book That Still Beats the Market.

- Bruce Greenwald – Professor and author of Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

- Bill Ackman – Founder of Pershing Square Capital Management